On the meaning and purpose of technology

In his later work, Martin Heidegger engaged with the nature of technology and the relationship of technology to humans and society. He particularly emphasized what kind of thinking is needed to engage in this process. Here, I will summarize some of his main points.

The speech “Gelassenheit” was delivered in Heidegger’s hometown Messkirch in 1955 (located between Black Forest, Danube Valley, and Lake Constance). There is an English translation from 1966 entitled “Discourse on Thinking” but it suffers from severe shortcomings. Many key concepts — from Heimat to Nachdenken to besinnliches Denken — are not adequately translated and the original meaning of the lecture cannot be fully understood based on the translation. Therefore, instead of simply posting the English translation, I will briefly discuss the main ideas of the speech. The German original can be found here.

Heidegger begins by suggesting that we live in an age characterized by a poverty of thought (Gedankenarmut), as expressed in the frequency of encountering thoughtlessness (Gedankenlosigkeit). He claims that this kind of thoughtlessness runs against human nature as humans possess the ability to think as part of their very essence.

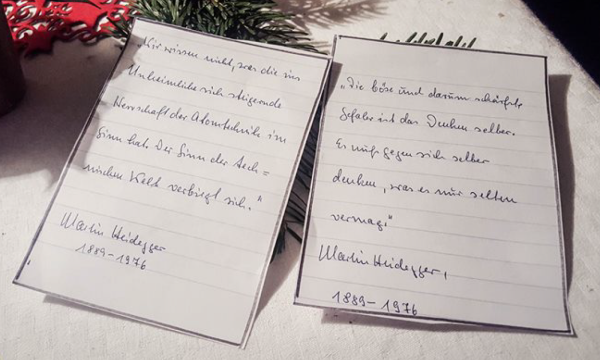

Heidegger then makes an important qualification as to the verb thinking — he distinguishes between two types of thinking: calculating thinking and reflective thinking (besinnliches Denken). By calculating thinking he means the kind of problem-solving within given constraints. In contrast, reflective thinking goes beyond that and involves reflecting on the purpose and meaning of things, a kind of thinking that strives after “the meaning which rests in everything that is.”

Next, Heidegger reflects on how in modern life the combination of media, entertainment, technology etc. leads to a kind of alienation which he describes as a loss of groundedness (Verlust der Bodenständigkeit). He finds that “in all areas of existence, humans are ever more closely surrounded by the forces of technical apparatuses and automation” and he suggests that this development will all the more accelerate in the coming decades.

His point though is not that such technological development is bad per se but he warns that humans are not adequately prepared for it — “that we are not yet capable, to think reflectively and engage in an appropriate examination with what is emerging in this day and age.”

He again proposes not to reject technology as this would be “silly” and “shortsighted.” Instead, his proposed solution for avoiding servitude to a technical world is to “use technological objects and simultaneously still remain free from them in such a way that we can let go of them at any time;” that we can use technical objects but still leave them as something “that does not affect us in our innermost and authentic” (im Innersten und Eigentlichen).

He concludes that we can say “yes” to the inevitable use of technical objects and at the same time say “no” to the degree that we prevent them from “preoccupying us exclusively and bend, confuse, and eventually let perish our essence.” In other words, “we let the technical objects into our everyday world and simultaneously leave them outside, i.e. let them be things that are nothing absolute but remain in themselves dependent on something higher.” This seeming contrast and tension between saying “yes” and “no” to the technical world, he calls “equanimity towards the things” (die Gelassenheit zu den Dingen).

Second, Heidegger notes that the meaning and purpose behind technical things remains still unclear but he proposes that “in all technical processes lives a meaning which draws on human action and acceptance, a meaning that has not just been invented and created by humans.”

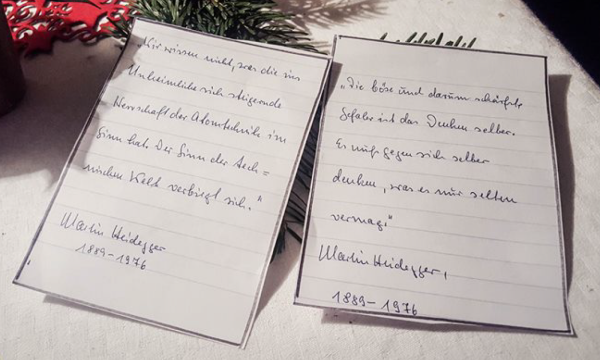

This is where the first quote in the picture below comes into play: “We do not know what is the meaning of the reign of atomic technology which accelerates into eerie heights. The meaning of the technological world is concealed.” Heidegger notes that we do not know the meaning of the unfolding technical world but we can nevertheless remain open and attentive to what could be its meaning. He calls this attitude the “openness to the mystery” (Offenheit für das Geheimnis).

In conclusion, Heidegger proposes that the combination of the “equanimity towards the things” and the “openness to the mystery” can help us retain a sense of agency, stay true to our human essence, and obtain a new form of groundedness in the technologically-shaped world of the present and future. This attitude “promises a new foundation and ground on which we can stand and persevere within the technical world without being threatened by it.” In contrast, Heidegger is concerned that the biggest threat is a loss of reflective thinking (which is a precondition for the above). If only calculating thinking prevails, he warns that the indifference towards reflective thinking, the total thoughtlessness, will lead to humans denying and throwing away their innermost, namely “that the human is a reflecting being.” He closes by saying that “this is why it counts to keep awake the reflective thinking.” However, “the equanimity towards things and the openness to the mystery will never fall in place on their own. They are nothing coincidental. Both only thrive out of ceaseless heartfelt thinking.”